Zinger Key Points

- U.S. banks profit from Fed's emergency program post-2023 SVB crisis, exploiting rate arbitrage for significant gains.

- This profit-making leads to a deferred asset for the Fed, impacting remittances to the U.S. Treasury for the upcoming years.

- Our government trade tracker caught Pelosi’s 169% AI winner. Discover how to track all 535 Congress member stock trades today.

American banks are generating profits out of thin air by exploiting an emergency funding program created by the Federal Reserve after the 2023 Silicon Valley Bank crisis.

A recent Wall Street Journal article by David Benoit and Eric Wallerstein sheds light on this arbitrage practice banks are using to generate windfall profits. The reporters identified a “free-lunch” situation where banks obtain Federal Reserve funding at a lower rate than what the Fed pays them for their reserve deposits at the central bank.

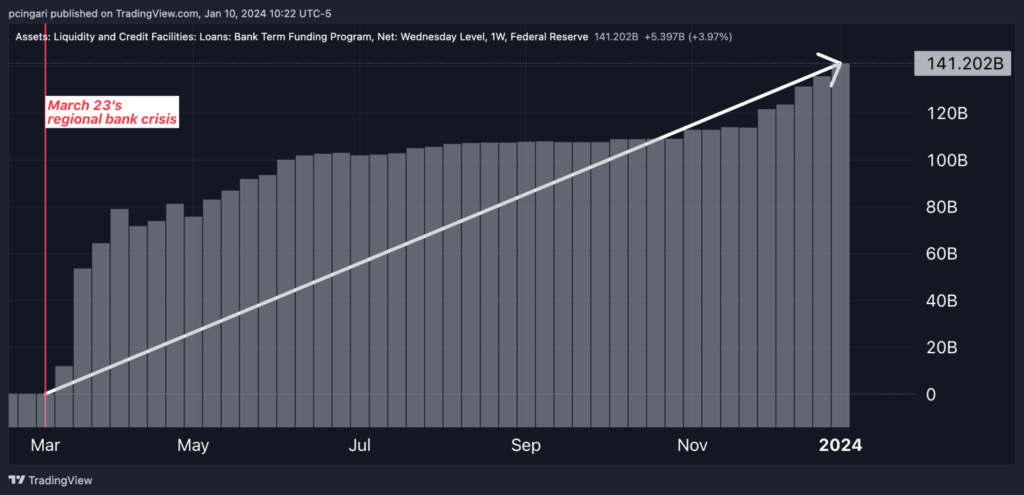

As of early January 2024, U.S. banks have borrowed a staggering $141 billion from the Fed's bank term funding program (BTFP) in just 10 months.

This program, offering loans of up to one year against collateral like U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, charges banks an interest rate based on future expectations — specifically, the one-year overnight index swap rate plus an additional 0.1%.

While the Fed offers financing below 5% through this rescue program, it concurrently pays banks 5.4% on parked reserve balances, leading to a risk-free profit margin of about 0.4% for the banks.

The Wall Street Journal quoted Janney Montgomery Scott analyst Christopher Marinac who said banks are exploiting a positive arbitrage.

Shares in the U.S. financial sector, monitored through the Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund XLF, have not only recovered but also exceeded their pre-March 2023 banking crisis values. Since late October 2023, these stocks have experienced a 20% surge, outperforming the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust SPY during the same timeframe.

In the past three months, leading U.S. banks have shown remarkable performance, with Bank of America Corp. BAC gaining 25%, Citigroup Inc. C rising by 30%, Goldman Sachs Inc. GS increasing by 22%, and Wells Fargo Inc. WFC advancing by 24%.

The Hidden Cost to U.S. Taxpayers

This lucrative situation for banks spells a cost for U.S. taxpayers. Interest payments the Fed makes on bank reserves are a liability for the central bank.

According to a November 2023 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the Fed’s liabilities, primarily bank reserves and reverse repos, constituted 59.5% of its total liabilities as of Nov. 8, 2023. With rising policy rates, the Fed pays more interest on these liabilities, but its assets, often locked at fixed rates, don’t yield proportionate returns.

This imbalance caused the Fed’s operating costs to surpass its income from September 2022.

Every year, the Fed typically turns over excess earnings to the U.S. Treasury, but with costs exceeding income, it has created a “deferred asset” — essentially a negative liability equal to the shortfall in earnings.

As of Nov. 8, 2023, this deferred asset amounted to $116.9 billion. The Fed is expected to return to positive net income in 2025, as per New York Fed estimates, but will carry the deferred asset until mid-2027, delaying remittances to the Treasury.

This means the U.S. Treasury will face a shortfall in cash transfers from the Federal Reserve until 2027, adversely affecting the federal budget, assuming other factors remain constant.

This emerging scenario underscores a hidden cost that ultimately falls on U.S. taxpayers.

Read Now: December Inflation Preview: What Will It Take To Trigger A Fed Rate Cut In Q1 2024?

Photo: Shutterstock

© 2025 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.