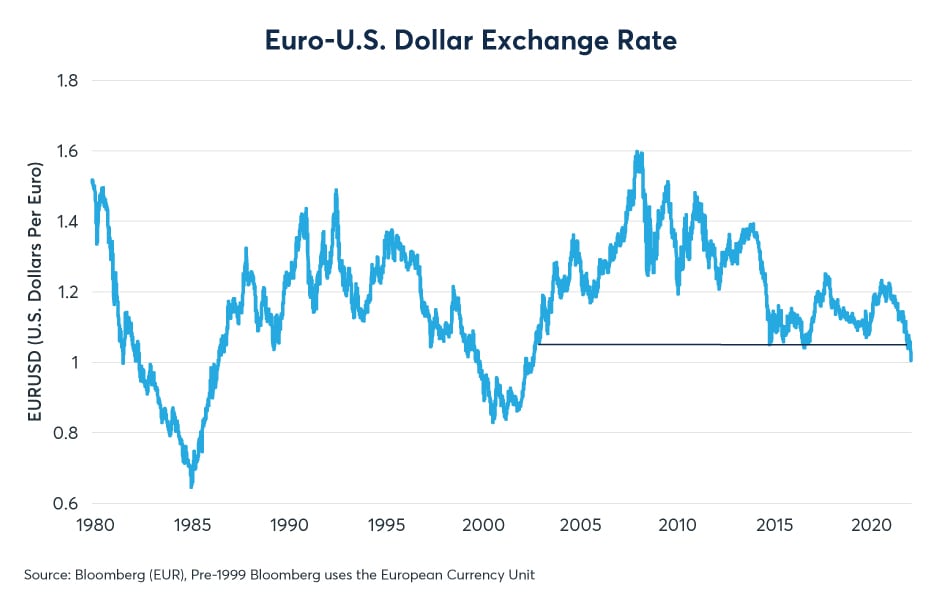

The euro (EUR) recently fell to its lowest level versus the U.S. dollar (USD) since 2002 after breaching a support level that has held up since 2015. (Figure 1). As EURUSD closed in on parity, the cost of options on the currency pair spiked to their highest level since March 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: EURUSD has fallen to a 20-year low but remains far above all-time lows

Scan the above QR code for more expert analysis of market events and trends driving opportunities today!

Figure 2: EURUSD implied volatility is at its highest since 2020

What caused the sharp decline in EURUSD? There are several factors, and they include:

- Monetary policy: the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) has been tightening policy much more aggressively than the European Central Bank (ECB).

- Trade balances: while both the U.S. and Europe have seen a deterioration in their trade balances, the eurozone has seen an especially sharp decline in its trade surplus in recent months as European natural gas prices soared.

- Fiscal policy: the U.S. budget deficit has been shrinking much more quickly than deficits in Europe.

- Intra-European bond spreads: increasing tension within the eurozone debt market also appears to be weighing on the euro.

Monetary Policy

The Fed has already hiked rates by 150 basis points (bps), and has signaled that it will likely raise rates another 50 or 75bps when it meets in late July. Meanwhile, the ECB has not yet moved policy although its President, Christine Lagarde, has indicated that it intends to make a first 25bps move in July, and may follow that up with another move in September. One-year forward differentials between U.S. and eurozone rates have often tracked EURUSD’s evolution. There have been exceptions, such as the period from 2017-19 when the U.S. pursued a tight monetary policy and a loose fiscal policy while Europe did the opposite. Nevertheless, from 2020 until about May 2022, the Eurodollar-Euribor future differential for contracts one year forward tracked EURUSD closely. Since then, expectations for ECB rate hikes have begun to catch up with expectations for further Fed rate hikes, but this has not been enough to support EURUSD, or at least not yet (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Differentials in expected future interest rates are among the factors that influence EURUSD

Another potential factor is quantitative tightening. As of June 1, the Fed began shrinking its balance sheet whereas the ECB has not. The relative movements in the two central banks’ balance sheets may also explain some of EURUSD’s recent weakness.

Trade Balances

Rate differentials explain a large part of the euro’s weakness over the past nine months but not so much what has happened with EURUSD in recent weeks. The most recent downdraft for the euro, which caused it to break previous support levels, might be better explained by trade, and specifically the impact of natural gas prices after Russia reduced supplies of the commodity to the European Union.

Over the past few years both the U.S. and the eurozone have seen their commercial balances deteriorate. Before going into the details, it is important to point out that the U.S. runs a structural trade deficit as a result of having the global reserve currency. By contrast, Europe sometimes runs deficits and sometimes surpluses. For EURUSD, what matters isn’t the deficit’s outright size, rather its relative direction. Smaller deficits most often equate to a stronger currency.

The U.S. trade deficit has grown from 3.9% to 4.9% of GDP over the past few years, while the eurozone trade surplus has come down from 3.5% to 1.8% of GDP. Europe’s trade balance might deteriorate further relative to the U.S. in coming months as European natural gas prices have soared to 9.5 times the Henry Hub prices in the U.S. (Figure 4). This price differential could boost U.S. exports and also increase the cost of European imports.

Figure 4: European natural gas now trades at 9.5x the U.S. price

Moreover, natural gas shortages in Europe imply difficult choices. For example, the German government has suggested that if gas rationing becomes necessary, they will favor continued supply to German households at the expense of cutting supply to German industry. As such, higher natural gas prices not only imply a rising import bill, they also portent possible reductions in manufacturing output and exports.

Budget deficits

From 2017 to 2019 the U.S. budget deficit was on a very different path than deficits in the eurozone. U.S. deficits grew from 2.5% of GDP to 5% while European deficits continued to shrink towards 1% of GDP. Following the onset of the pandemic deficits grew in both Europe and the U.S., but they expanded far more quickly on the U.S. side of the pond, eventually approaching 20% of GDP – about twice the level as Europe. Expanding U.S. deficits counteracted a tighter monetary policy from 2017 to 2019, preventing the dollar from strengthening much and then exacerbated the dollar’s weakness in 2020 and 2021 at the onset of the pandemic.

However, beginning Q2 2021 the U.S. budget deficit began shrinking rapidly and the U.S. is now running smaller fiscal deficits than the eurozone for the first time in two decades. Typically, smaller deficits equate to a stronger currency and the rapid shrinking of the U.S. budget deficit appears to be a factor supporting the U.S. dollar (Figure 5 and 6).

Figure 5: U.S. deficits are rapidly shrinking after having outpaced Europe from 2017-2021

Figure 6: A smaller U.S. budget deficit may be supporting USD versus EUR

Intra-European Bond Spreads

While the ECB has not yet ended QE, the prospects of tighter monetary policy and possible balance sheet reduction have coincided with a sharp rise in European bond yields, but with especially sharp increases in yields in nations with higher levels of public debt such as Italy. Wider sovereign spreads between Germany and nations like Italy appear to be weighing on the euro (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Widening spreads among eurozone sovereign bonds can pose a challenge for EUR

The ECB says that it will put in place a mechanism to prevent excessive widening of spreads between the various eurozone nations. It has not, however, spelled out any details, but preventing spread-widening may prove tricky for the ECB as its mandate forbids it from favoring the debt of one eurozone nation over another.

As we have discussed in a recent paper, a great deal has changed since the last eurozone crisis from 2009 to 2012. Since then, certain nations including Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain have significantly deleveraged while others including Belgium, Finland and France have seen debt levels soar (related content here). In France, corporate debt levels are especially high and one risk is that corporate debt could eventually be brought onto the public books. Indeed, this may already be happening with the French government’s move to nationalize the heavily indebted Elecricité de France.

This post contains sponsored advertising content. This content is for informational purposes only and not intended to be investing advice.

© 2025 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Comments

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.