Why marry a put?

Options jargon can easily drive people nuts, whether they are novice or seasoned. Some names for certain strategies are certainly more intuitive than others. I’d like to think that the “Married Put” term is in the quasi-intuitive category. Regardless, I am going to spend the next dozen or so paragraphs addressing not only the definition, reasoning, and risk of the strategy, but also to address some of the questions we received during Tuesday’s Two Traders, One Strategy webinar. I encourage all of you to join us for this presentation every Tuesday at 4:30 p.m. Eastern Time. You can register here; it’s free.

Married Put Defined

The married put is just that; it’s a long put married to (combined with) long stock. It is a strategy that can be used to set a “stop limit” or to hedge your long stock position to the downside. For every 100 shares of stock a trader is long in her account, she would purchase one put to create the married put strategy. Off the bat, this may seem a bit strange; buying stock (a typically bullish act) but simultaneously buying a put (a bearish act)? The popular covered call strategy has a similar dichotomy (long stock, short call), but let me explain why the married put is quite different.

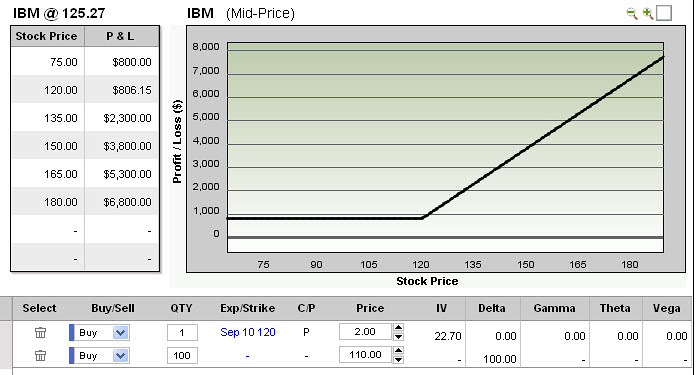

If you examine the risk graph above, you’ll notice that it looks completely different from the covered call. The married put strategy still offers unlimited upside potential, indicated by the 45-degree angle at the right half of the graph, above the breakeven point. On the left half of the chart, below the breakeven point, you will notice the line is flat, meaning that downside is limited. So in theory, this is a limited downside strategy, with unlimited upside; that sounds great, doesn’t it?

Well, as great as it sounds, you know that there is no such thing as a free lunch in the options world. There is always a caveat and in this case, the caveat is the cost of the put and its decay over time. Looking again at that risk graph, you may notice it looks exactly like a long call. With a long call, at expiration, your breakeven for the trade is the strike price plus the premium you paid. In the married put, your breakeven is your stock cost basis plus the put premium paid.

Mechanics and Risk/Reward of the Trade

So let’s assume that we owned IBM at $110 (as indicated in the above graph). As of Wednesday’s close, IBM stock is currently trading at $125.27, which means a profit of $15.27 in the stock. Obviously, we could choose to just hold the stock or sell it. But what if there was an earnings report or we felt the market had been rallying for a week and could be due for a temporary (but perhaps sharp) pullback? This might be a time to consider buying a long put.

Remember, the put’s value should rise if a stock is dropping, as the put provides the right to sell that stock at the strike price on or before expiration. Unlike a covered call, which has limitations on how much it can actually hedge the underlying stock, the long put can completely limit downside risk in a trade and in some cases ensure a profit, no matter what the stock does.

If the stock drops to a point at which it seems likely to rally again, we could always buy the put back (potentially for a profit) and allow the stock to rally by its “unmarried” self. In that case, we would have lowered the net cost basis in the stock with the profit brought in from the put trade. This doesn’t always happen in the real world. Maybe the stock continues to drop, stays flat, or maybe we mis-time the entire trade. This is why it’s paramount to not only know what you are trading, but to have some sort of game plan in place beforehand. So let’s get back to the trade…

Picking the Strike and Expiration

Because we were lucky enough in this case to own the stock much lower, we have quite a bit a profit to work with. When buying a put, you are actually adding to the net cost of the stock trade, thus raising the breakeven. Picking a strike involves a couple of different factors, the first of which is how much you actually want to spend. If, for example, you buy an out-of-the-money put, hold it until expiration (which you don’t have to, by the way) and the stock stays flat or moves higher, you could lose 100% of your premium. Of course that may be okay, because you have the peace of mind knowing that you have an effective stop-loss in place to hedge your downside. This is when you really need to think about what the stock can potentially do as well as how potentially fragile the broad market may be.

In the above case, a trader’s rationale might be that he would be comfortable locking in an $800 profit for the next 60 days. The $800 was derived from simply by taking the put strike of 120, then subtracting what was paid for the stock ($110), then subtracting the $2.00 premium paid for the put, equaling $800. So as long as the option did not expire, even if the stock went to zero, the trader would still have an $800 profit and upside would be unlimited.

Now, if and when the trader sells the option, he must add or subtract any profit or loss in that option trade to his net basis in the stock, in order to accurately track the P&L. If the option expires worthless, he must add the put premium to the net cost. This may make it harder for a trader to make money in the future, as it requires a more dramatic move in the shares. A different trader could use another kind of options strategy that brings in income, like a covered call, to potentially offset these costs. The covered call carries its own set of risks as well.

Choosing an expiration month really depends on cost and the amount of time you want to hedge your stock. It is truly a personal preference. If you are losing money in the stock position, buying a put may add to your cost and put you more in the hole, so be sensitive to your total cost in the trade. Lastly, be aware of the theta of the put you buy (how much it will cost you per day) as well as the acceleration of the theta you may endure as that option moves closer to expiration.

Summary

The Married Put strategy is a synthetic long call, meaning you are paying time decay (the premium of the put) to enter the trade. It has limited downside and unlimited upside. It is ultimately a bullish trade, but you can trade in and out of the put while maintaining your stock position. The married put can also be used to set a very rigid stop limit in your long stock position (typically once you are already at a profit). The married put has an advantage over a traditional stop loss or limit in that it will limit your risk to a finite amount even if the stock gaps down, which a stop order may not. Consider trading it in your virtual account to learn its very unique behavior and to work on strike and expiration selection.

OptionsHouse does not offer tax or legal advice. Please consult your tax advisor to determine how your cost basis is calculated for specific trading strategies.

Photo Credit: Molly Germaine

Share and Enjoy:

Related posts:

© 2024 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Comments

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.