In the five years since the British parliament passed a law calling for a referendum on whether the UK should remain in the European Union or leave, there have been many intervening moments affecting the global economy, including the Brexit vote itself in 2016 and now the coronavirus pandemic.

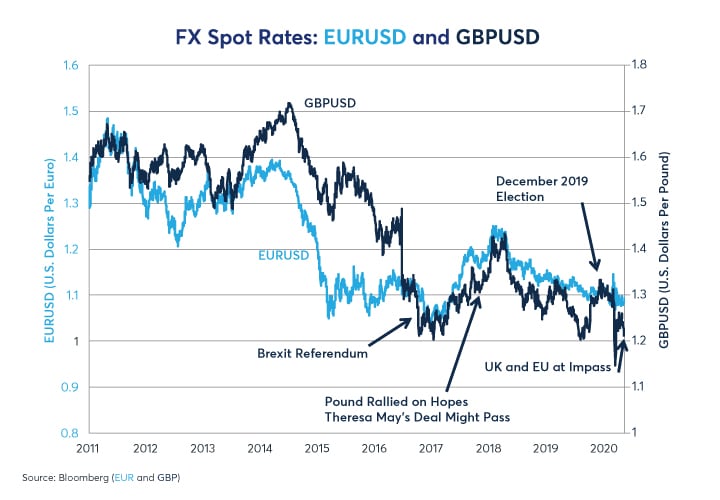

During this time, one element has remained constant: the British pound (GBP) rallies when the UK moves toward deeper integration with Europe, and falls when the UK moves towards a no-deal Brexit decision. Investors were reminded of this once again in early May as the UK and EU negotiations hit an impasse, with both sides citing a lack of progress on issues ranging from fishing rights to business-competition regulations. Since the negotiations stalled, the pound has slid 3% versus the euro (EUR) and 4.5% versus the US dollar (USD).

This is the latest installment in a longstanding theme:

- Between the time the UK Parliament called the referendum on June 9, 2015, until the referendum itself on June 23, 2016, GBP slid 4% versus EUR and 3% versus USD.

- In the months after the referendum, GBP plunged 17% versus EUR and 21% versus USD.

- Since the referendum, GBP has tended to rally when it looked like a deal was close (+21% versus USD into early 2018 as then Prime Minister Theresa May held negotiations) and tended to sell off when Brexit appears to be headed towards the “no-deal” scenario (-16% when May’s deal was repeatedly defeated) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: GBP rallies on hopes for more integration with Europe, sells off with less integration

Negotiators will meet once more in early June 2020 to decide if it’s worth continuing the discussions. The UK government’s EU Exit Operations (XO) committee — also commonly known as the “no-deal planning unit” is meeting more regularly. The UK government denies that it will extend UK membership in the Common Market beyond December 31, 2020, however, it is possible the economic damage from the pandemic could nudge them to seek some sort of delay, particularly if no acceptable deal is in place.

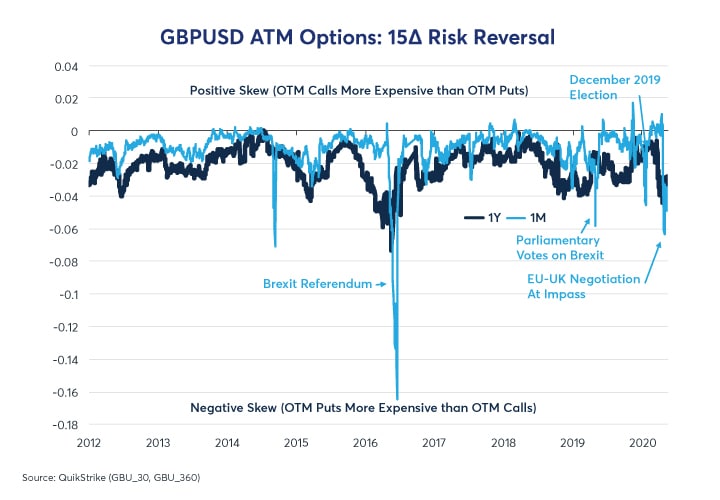

Going into this next round of negotiations, GBP options markets are more skewed to the downside than usual with out-of-the-money (OTM) put options substantially more expensive than usual compared to OTM calls. By May 19, the options skew (also called risk reversal) was more negative than it had been 92% of the time during the previous two years. Options traders have, at times, proved prescient with respect to future moves in the pound: options skew was extremely negative in the lead up to the 2016 referendum and, indeed, GBP collapsed after the result became apparent (Figure 2). Skewness isn’t as negative this time, but pound options are considerably more expensive than those on EUR when seen from a USD perspective (Figure 3). Moreover, most of the recent spikes in both implied volatility and risk reversal have been motivated by concerns over the progress of Brexit negotiations. The one exception occurred during an incipient dollar-funding crisis in mid-March. After the US Federal Reserve stepped in, that issued was resolved quickly.

Figure 2: GBP 1M and 1Y options are more negatively skewed than usual

Figure 3: GBP option implied volatility, typically similar to EUR pre-referendum, is now higher

UK interest rate markets have shown less reaction to Brexit-related events than the currency market. The Bank of England (BoE) is focused on containing the economic damage from the pandemic and interest rate traders are debating whether the BOE will follow the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank down the path to negative interest rates (Figure 4). If the BoE does go negative, it might have unexpected consequences for exchange rates. Of the four central banks which went to negative rates during the past decade, two of them quickly saw their currencies strengthen. The other two had more mixed results, yet were still consistent with the concept that negative rates do not work as intended. Sweden has already exited negative-rate territory. Coming soon, our report on “What FX Markets Say About Negative Rates.

Figure 4: SONIA futures price a possibility of negative rates in the UK

Normally a stronger currency is a sign of a relatively tighter monetary policy. While negative rates are meant to loosen monetary policy and support economic recovery, they instead can act as a tax on the banking system and may interfere with the process of credit creation. An inadvertent and undesired tightening of monetary policy that stems from negative rates may explain, in part, why currencies subject to negative deposit rates have tended to strengthen rather than weaken as is commonly the case when central banks ease monetary policy.

While its uncertain if the BoE will decide to push rates below zero, if the central bank were to pursue negative rates, it might strengthen the pound. A stronger currency could, in turn, slow the recovery from both the pandemic as well as making it more difficult to absorb any additional shocks from a possible no-deal Brexit.

Finally, when it comes to the pandemic, other than obliging the BoE to quickly return to near-zero rates and implying a vast expansion of the UK’s budget deficit, the pandemic appears to have had a limited impact upon the pound beyond the transitory dollar-funding issues in mid-March. For the moment, the UK’s economic and fiscal situation in the face of the pandemic very much resembles that of its neighbors across the Channel and across the Atlantic.

One question for the pound post-Brexit is whether it will begin to trade more like the Australian (AUD) or Canadian dollar (CAD)? We think that this is unlikely. Even post-Brexit, GBP could probably remain in EUR’s orbit for a number of reasons, not least of all because over 40% of Britain’s exports go to the European Union. Even if that number drops a bit under a no-deal Brexit scenario, UK’s trade with Europe is likely to far exceed its trade with any other country. Secondly, the UK ceased to be a net exporter of oil over a decade ago and with North Sea reserves dwindling and the UK having no other substantial domestic commodity production, there is little reason to think that GBP will begin to trade like AUD, CAD or other resource-dependent currencies.

Bottom Line

- GBPUSD and GBPEUR depend on post-Brexit trade deal negotiations

- GBP options remain skewed to the downside

- SONIA futures price a possibility that the BoE will pursue negative rates

- GBP typically rallies when the UK moves towards deeper integration with Europe

To learn more about futures and options, go to Benzinga's futures and options education resource.

© 2025 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.