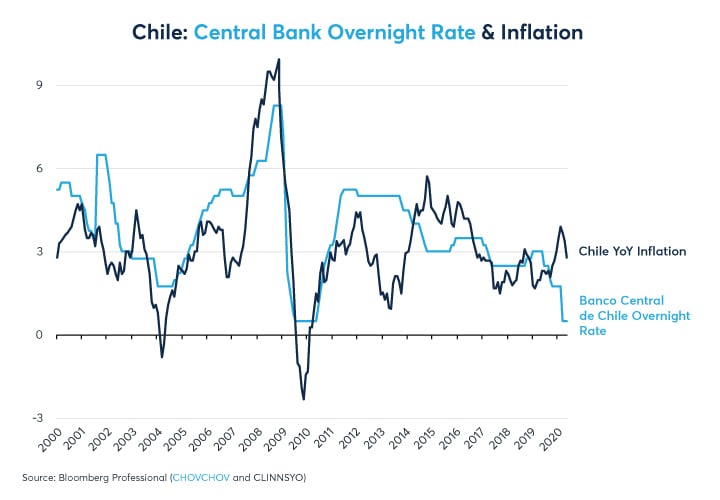

Like many of its regional peers, Chile’s economy has been hard hit by the coronavirus. But unlike other Latin American countries that have slashed interest rates to record lows, Chile’s central bank has gone one step further to become the first to put short-term interest rates close to zero (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chile has the highest debt among LATAM countries and, by consequence, the lowest rates

The bank has cut rates to 0.5%, matching the lowest level ever in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis (Figure 2), with its overnight lending rate now nearly 2% below the trailing rate of year-on-year inflation.

Figure 2: Banco Central de Chile has slashed rates to their 2009-10 record lows; real rates are negative

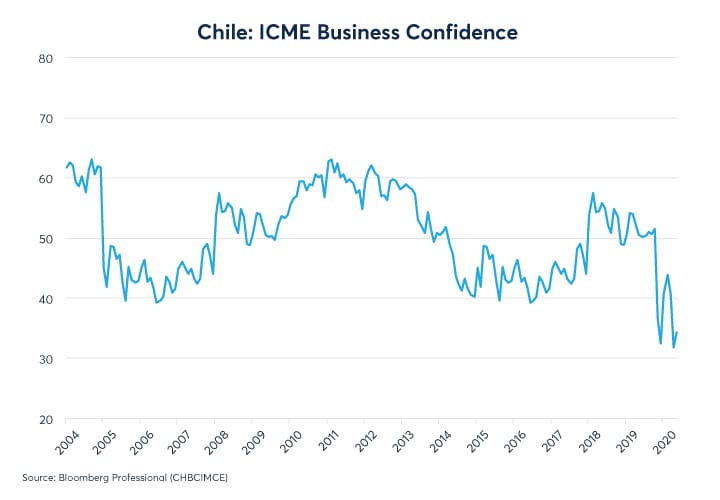

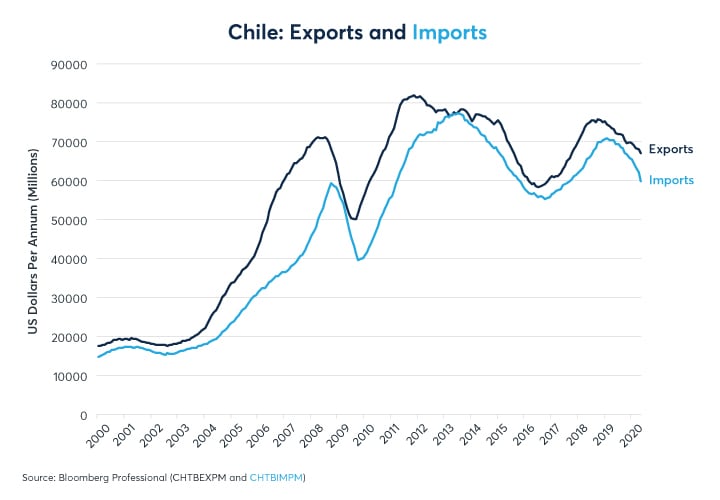

The backdrop to the central bank’s monetary policy initiatives is the fall of Chile's economy by about 15% year-on-year in April (Figure 3). Vehicle sales have plunged to levels last seen during the global financial crisis (Figure 4) and business confidence has remained slack in May and June (Figure 5), suggesting that economic activity remained weak throughout Q2. In addition, the downtrend in imports and exports has accelerated (Figure 6) while unemployment reached a 10-year high (Figure 7).

Figure 3: Chile’s economic activity fell by 15% YoY in April

Figure 4: Vehicle sales have plunged to 2009 levels

Figure 5: Little recovery in business confidence suggests growth remained weak in May and June

Figure 6: Chile’s imports and exports were already weak before the pandemic struck

Figure 7: Unemployment has surged to a 10-year high

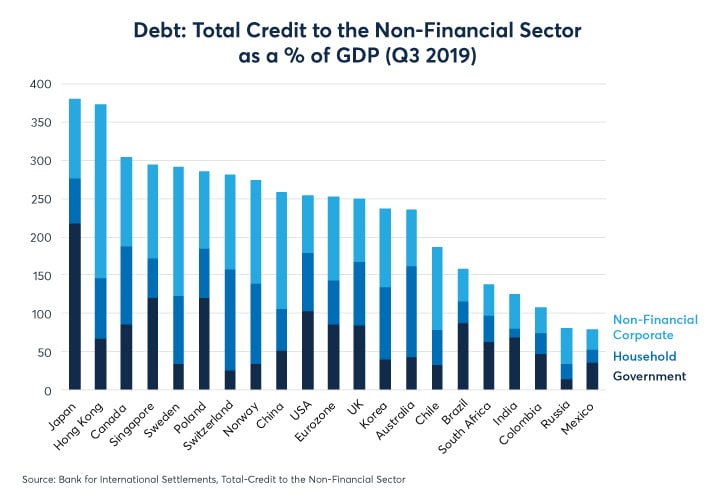

Part of the reason why Chile’s rates are well below those in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico is that Chile has relatively higher levels of debt (Figures 8 and 9). Total public and private sector debt is nearly 190% of GDP – not as high as countries like China, US or Western European nations but much higher than in most other emerging markets.

Figure 8: Chile has much higher levels of debt than Brazil, Colombia or Mexico

Figure 9: Chile debt levels have been rising

Brazil’s debt totals 160%, Colombia’s is close to 120% and Mexico’s is only 80%. Measured as a percentage of GDP, Chile’s debt levels are much higher than they were in 2009 and 2010, the last time its central bank cut rates to 0.5%. Back then, the total debt was around 120% of GDP. The rise in public and private sector debt burdens over the past decade suggests that Chile’s central bank may need to keep interest rates low for a much longer period and perhaps even cut them further towards zero. High debt burdens may make Chile’s economy less responsive to lower interest rates than during the aftermath of the global financial crisis when debt levels were much lower and economic growth surged as China, the main buyer of Chile’s copper, and other nations took on massive stimulus efforts.

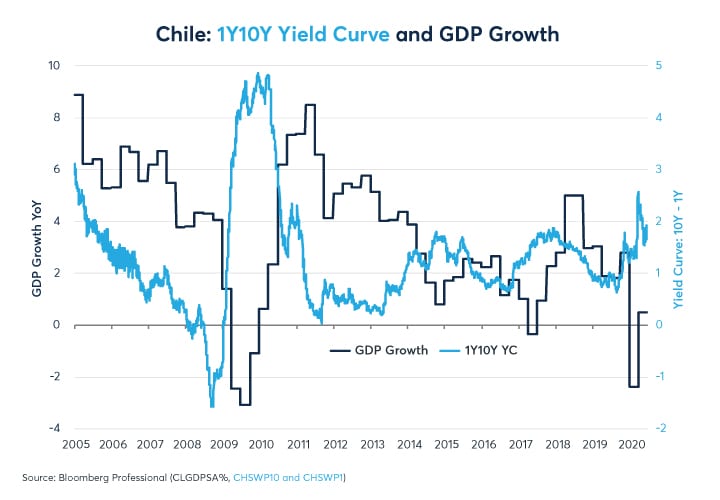

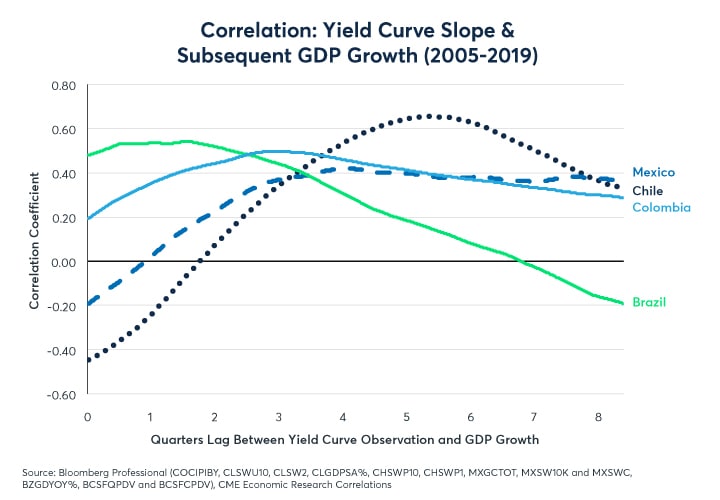

That said, Chilean interest rate markets are optimistic about the prospects for recovery. In May and June, Chile’s 1Y10Y yield curve (the difference between 10-year and one-year interest rates) was at its steepest since 2011 – though still a far cry from its steepest levels of 2010 (Figure 10). Over the past 15 years, Chile’s yield curve has exhibited a strong positive correlation of up to +0.7 with GDP growth 4-6 quarters in advance (Figure 11). As such, if history is any guide, Chile may return to solid growth rates in 2021.

Figure 10: Chile’s yield curve suggests an optimistic outlook regarding a possible 2021 recovery

Figure 11: Chile’s yield curve correlates positively with growth 4-6 quarters ahead

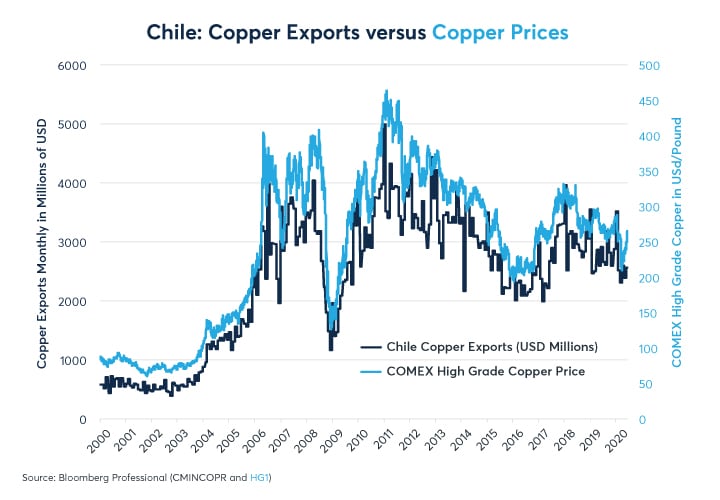

Meanwhile, the value of the Chilean peso (CLP) remains closely tied to the global price of copper. CLP broadly follows an index of commodity prices weighted to reflect their share (in percentage) of the export market (Figure 12). Copper accounts for nearly half of Chile’s exports (Figure 13) and the value of Chile’s copper exports move in tandem with the COMEX high-grade copper price (Figure 14).

Figure 12: The Chilean peso hasn’t rebounded as much as commodities have in recent weeks

Figure 13: Copper accounts for nearly half of Chile’s exports

Figure 14: The dollar value of Chile’s copper exports closely tracks the COMEX price

Copper prices have rebounded from their recent lows. The reason, however, is not an encouraging one. While demand has picked up in some places like China, it remains severely depressed compared to its pre-pandemic levels. The rebound has much more do with mines being forced to shut down in Peru and Zambia due to the pandemic. Peru accounts for 12% of global copper supplies, and Zambia an additional 8%. Chile remains the most important producer, with a 28% global market share. Currency traders seem to be looking beyond the temporary supply disruptions in Peru and Zambia towards potentially weakened demand for the metal going forward. This may be due in part to Chile’s labor unions requesting meetings about possible mine shutdowns there as well as the virus spreading in the country.

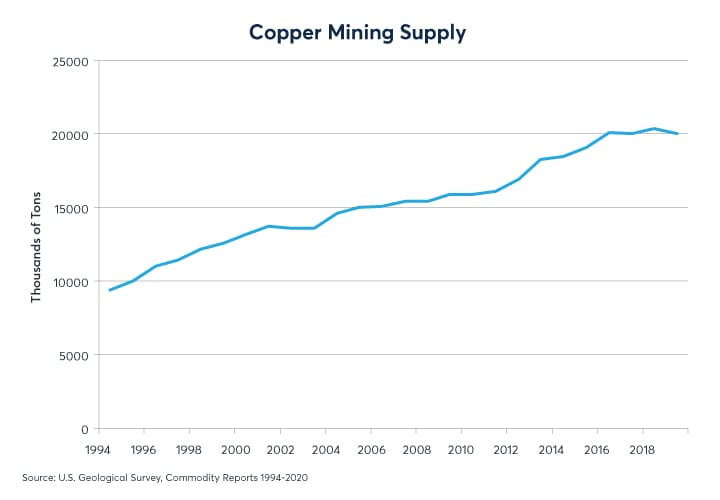

More broadly, global copper production is double what it was 25 years ago in 1994 (Figure 15). This may pose challenges for copper exporters such as Chile if the global economy and demand for copper don’t recover quickly. As such, the future direction of Chile’s currency and economy may depend heavily on the strength of economic recoveries in China, Europe, the US, and their impact on global copper demand.

Figure 15: Copper mining supply has grown exponentially

Bottom Line

- Chile’s central bank is running out of room to cut rates further

- High debt levels could keep Chile’s rates low for a long time

- Chile’s peso and economy closely track the price of copper

- Copper prices bounced on mine shutdowns in Peru and Zambia but demand remains depressed

To learn more about futures and options, go to Benzinga’s futures and options education resource.

© 2024 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Comments

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.