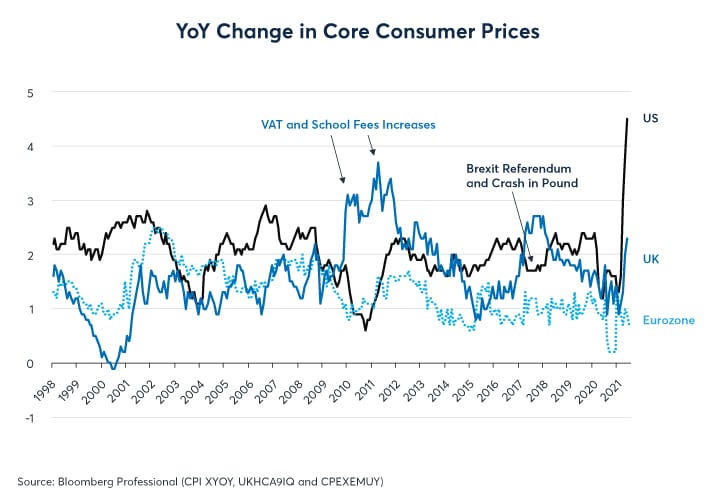

After U.S. inflation surged 5.4% in June from a year earlier in its biggest monthly gain since August 2008, it once again rose 5.4% in July. Even when excluding food and energy components, inflation rose 4.3% year-over-year for the month of July. This surge in consumer prices seems to be unique to the United States, at least in comparison with the world’s largest economies.

The U.K. has seen some rise in inflationary pressures but nothing like what has happened in the United States. U.K. core inflation is still below 2.5%, although it is up from a pandemic low of around 1%. Meanwhile, eurozone core inflation is around 1%, only half of the European Central Bank’s theoretical target of “just below 2%.”

U.S. inflation has surged ahead while European inflation has not

Contributing Factors

Part of the reason for higher U.S. inflation relates to used car prices, which are 3.7% of the index weighting and up 45% year-over-year. Even excluding used cars, U.S. headline inflation would still be running at 4% year-over-year, far higher than in Europe or elsewhere. Meanwhile, the U.S. housing sector has not been a major contributor to rising U.S. inflation. Rental costs and so-called “owners’ equivalent rent” — the amount that owners would hypothetically pay themselves in rent if they rented their properties rather than owned them — are up only about 2.3% year-over-year. Outside of housing, U.S. inflation is about 0.7% higher than the headline figures suggest.

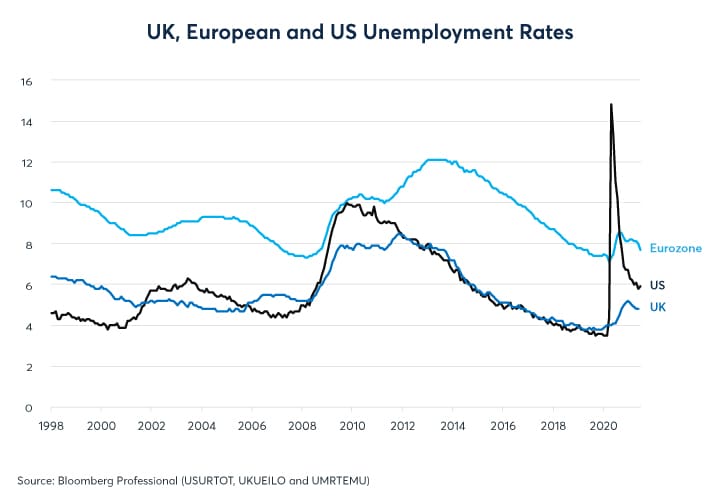

Labor Market Crisis

The U.S. inflation situation appears to be unique and may be the result of the country’s way of handling the labor market crisis during the pandemic. Although European responses varied somewhat by country, governments generally mitigated lockdown-related unemployment by lending money to employers to keep workers on staff and making those loans forgivable so long as workers were not laid off. As such, when lockdowns ended and businesses reopened, workers simply returned to their previous jobs. The rise in U.K. and eurozone unemployment was fairly modest because even when they were not able to show up for work, most workers in these nations were still technically employed and on payroll.

By contrast, U.S. employers laid off workers in droves in March and April 2020, sending the unemployment rate soaring from 3.5% to 14.8%. These workers could then apply for enhanced unemployment benefits, which untethered them from their previous employers. Depending on the state, the enhanced benefits lasted for 15-18 months, and for many low-wage workers, the benefits paid about the same, and in some cases more, than their previous employment. Meanwhile, some workers relocated, moving in with friends or family members. Some left high-cost areas like New York and San Francisco to live in areas with lower costs of living.

As the U.S. economy began to reopen, this meant that workers were not necessarily able to return to their previous employers even if they wanted. This in turn sent employers scrambling for talent, in some cases offering signing bonuses or wage increases in order to entice workers back. Nothing comparable appears to be happening in Europe.

Moreover, the shortage of workers aggravated supply chain issues in the U.S. In the rest of the world, there have been supply-line problems pertaining to shipping containers and extremely strong demand for manufactured items, but these issues have not, by all appearances, generated the kind of inflationary pressures that so far seem to be peculiar to the U.S.

Europe loaned money to employers to keep workers on payroll; U.S. workers were laid off.

Leaving Lockdown

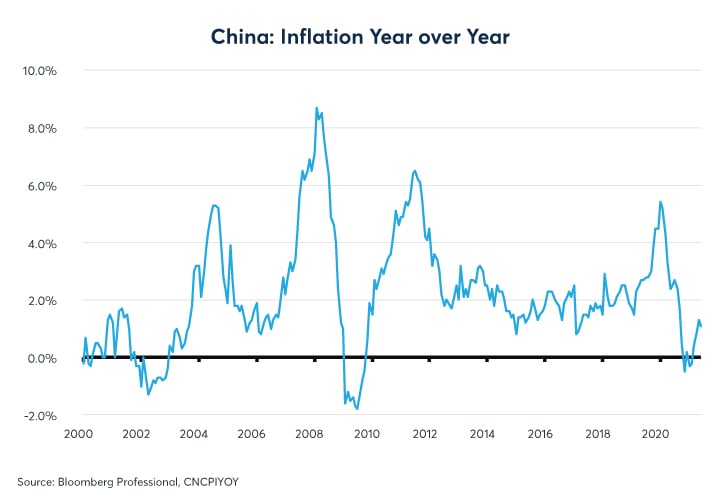

There are other possible explanations for the resurgence of inflation in the U.S. and the lack of it in Europe. One hypothesis holds that inflation rose sharply in the U.S. because the country came out of lockdowns quicker than most European countries. If this is true, then perhaps Europe will see higher inflation in the months ahead now that its vaccination rates have caught up to and surpassed that of the U.S. That said, China, the world’s second-largest economy, emerged from lockdown before just about anyone else, and inflation in China is lower today than it was before the pandemic. It has come in around 1% year-over-year in recent months as Japanese inflation remains at around zero.

Chinese inflation rates are lower now than pre-pandemic

Another possibility is that the U.S. fiscal response was more massive than other countries, offering economic impact payments to most American families, whether they needed it or not. This may have fueled a consumer spending boom that has not seen a parallel in Europe or elsewhere.

If higher U.S. inflation is really just a result of the different tactics the country took to handle the pandemic’s impact on the labor market, this lends credence to the Federal Reserve’s view that the rise in inflation will be “transitory.” This is a view that also appears to be endorsed by the bond market, which has not been perturbed by the recent surge in inflation. Even as Q2 2021 inflation rose as at an annualized pace of 9-10%, bond yields fell and continued to go lower in the first month of Q3. Moreover, breakeven inflation spreads have settled at around 2.4% on 10-Year Treasuries.

With enhanced unemployment benefits expiring nationwide at the end of September, the key test of this “transitory” inflation hypothesis will be whether workers rush back into the labor market in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022, alleviating labor shortages, supply chain issues, and inflationary pressures in the process.

Image by Foto-Rabe from Pixabay© 2024 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Comments

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.